Introduction

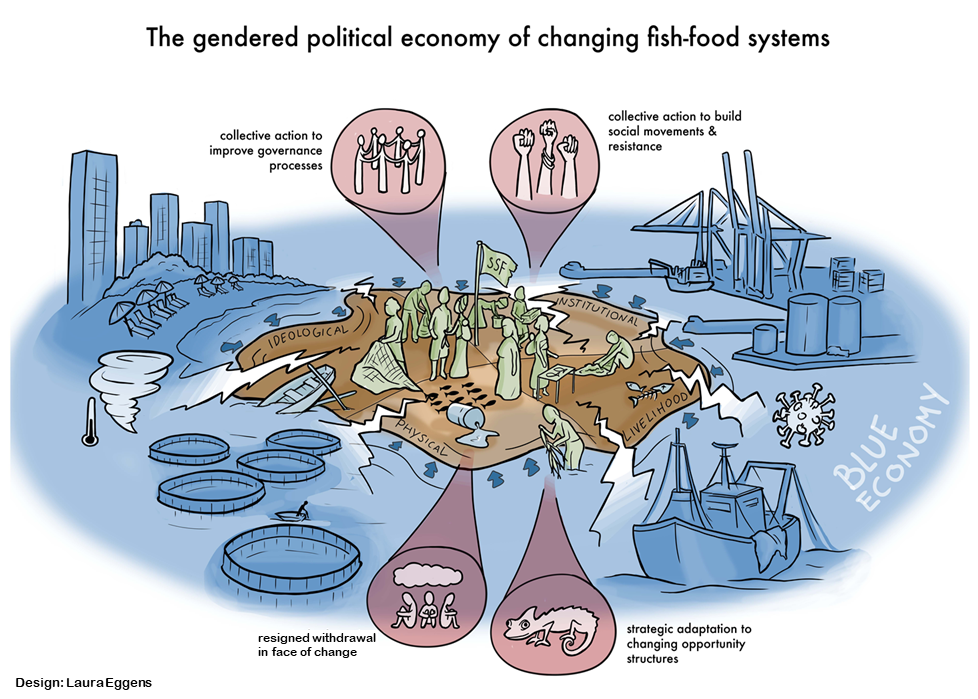

While these developments promise economic growth, we asked the question, who is benefiting from this?

Our findings reveal a concerning narrative: the shrinking physical, economic, socio-cultural and political space for local communities who rely heavily on marine resources for their livelihood. From India’s coastal aquaculture conflicts to Sri Lanka’s market disruptions, Kenya’s resource-use conflicts, and Cambodia’s tourism-induced fishing constraints, this research highlights the urgent need for a just, inclusive approach to development and Blue Economy initiatives.

- Presented at the MARE Conference People & the Sea XI - 28 June to 2 July, 2021.

- Presented at the 8th Global Conference on ‘Gender in Aquaculture & Fisheries’ - 21-23 November, 2022.

While these developments promise economic growth, we asked the question, who is benefiting from this?

Our findings reveal a concerning narrative: the shrinking physical, economic, socio-cultural and political space for local communities who rely heavily on marine resources for their livelihood. From India’s coastal aquaculture conflicts to Sri Lanka’s market disruptions, Kenya’s resource-use conflicts, and Cambodia’s tourism-induced fishing constraints, this research highlights the urgent need for a just, inclusive approach to development and Blue Economy initiatives.

Sri Lanka

- Women traders face significant economic hardships; lacking in savings and ridden with financial constraint

- In the Pitipana market, women vendors, often dealing with smaller fish volumes, are not recognised as ‘vendors’ by their male counterparts who trade larger quantities. This marginalisation extends to the physical space of the market, where women are confined to roofless corridors, while men occupy the more desirable interior spaces.

- Sri Lanka’s marine fisheries, supporting over 185,000 households and 2.7 million related households, could benefit immensely from the inclusion and empowerment of women. More importantly, fisherwomen deserve recognition and space to engage in the sector, if they choose to do so.

- While Blue Economy investments aim to benefit various societal actors, they often result in small-scale fisheries, particularly those run by women, being squeezed out of geographic, political, and economic spaces.

Ramanathapuram, India

- In the East Coast of India, especially in fishing villages like Ariyankundu and Sambai, there’s a growing conflict between aquaculture farmers and women engaged in seaweed farming. This tension underscores the need to balance commercial aquaculture with the livelihoods of artisanal fishers.

- There’s a significant gap between policy proposals and reality. Aquaculture farms often operate in ecologically sensitive areas and fail to comply with regulations set by authorities like the Coastal Aquaculture Authority (CAA).

- The Blue Economy’s impact is distinctly gendered, affecting women the most. Women play a crucial role in their communities, from collecting water for family and livestock to engaging in ancillary fishing activities. However, the Blue Economy has not delivered on many of its promises to these artisanal communities.

Honnavara, India

- Honnavar, a pivotal location in the study, vividly demonstrates the disruptions caused by Blue Economy developments to the local fishing communities. These changes, while aimed at economic growth, have profound implications on the traditional livelihoods and environmental balance.

- The natural dynamics of the river mouth in Honnavar are undergoing significant changes due to proposed developments, such as new fishing harbous and ports.

- Karnataka’s introduction of Blue Flag beaches, a part of eco-tourism initiatives, presents an environmental paradox. These beaches are nice and clean, but right next to them, it’s a garbage dumping ground.

- Over 30% of the catch by small-scale fishermen comprises plastics, indicating severe marine pollution and its impact on local fishing livelihoods.

Kenya

- In Kenya, women are actively involved in various community projects linked to the Blue Economy. These include seaweed farming, fin fish farming, eco-tourism ventures, and environmental conservation efforts.

- The absence of specific regulations guiding the Blue Economy has led to uncontrolled development and expansion, often at the cost of traditional fishing practices and environmental sustainability.

- The planned construction of Shimoni fishing port exemplifies the direct impact that Blue Economy initiatives could have on local fishermen. The development is projected to lead to the loss of vital fishing grounds and seaweed farming areas, significantly affecting the livelihoods of local fisherfolk and the community at large.

- Efforts are underway to address conflicts arising from the Blue Economy through Marine Spatial Planning. This approach involves organizing and managing the use of ocean space to reduce conflicts and environmental impacts.

Cambodia

- Beach extensions and eco-tourism projects, combined with sand sedimentation, have altered the coastline. This has resulted in shallower waters, making it difficult for fishermen to dock their boats.

- There is a divide within communities in the coastal villages of Kampot and Kep, with some villagers supporting coastal investment and others actively opposing it.

- There’s a significant miscommunication with the government regarding the needs of the coastal fishing communities. Only a few voices are heard, often not representing the majority, leading to decisions that do not address the broader community’s needs.

- The surge in tourism and coastal development, primarily fueled by local investments, has significantly impacted villagers in areas like Kampot, leading to a widespread sense of disempowerment. Amidst these changes, some fishers are adapting by diversifying their livelihoods, employing this strategy as a means to cope with the evolving landscape.

- While men in these communities are grappling with feelings of disempowerment, women are taking a more active stance, persistently and resisting the ongoing changes in their environment.

About the study

The objective of the project is to investigate the impact of environmental and economic “ruptures” on small-scale fisheries in the greater Indian Ocean region and how these are mediated by intersectional social relations: gender, ethnicity/race, caste, class, and place.

The project convenes an international, interdisciplinary collaboratory of scholars who conduct research on small-scale fisheries in four countries across the greater Indian Ocean region.

Research Team

Gayathri Lokuge, PhD

Principal Investigator (PI) Center for Poverty Analysis, Sri Lanka

Holly Hapke, PhD

Co-Principal Investigator University of California, Irvine

Amalendu Jyotishi, PhD

Co-Principal Investigator Azim Premji University, India

Karin Fernando

Center for Poverty Analysis, Sri Lanka

Derek Johnson, PhD

University of Manitoba, Canada

Kyoko Kusakabe, PhD

Asian Institute of Technology, Thailand

Ajit Menon, PhD

Madras Institute of Developments Studies, India

Betty Nyonje, PhD

Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute

Francis Okalo, PhD

Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute

Ramchandra Bhatta

Snehakunja Trust, Honnavara, Karnatka, India

Prabhakar Jayaprakash

Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai

Nadiya Azmy

Center for Poverty Analysis

Channaka Jayasinghe

Centre for Poverty Analysis, Sri Lanka

Bhagath Singh A.

Department of Social Sciences, The French Institute of Pondicherry, India

Joeri Scholtens

Center for Maritime Research, University of Amsterdam

Prasanna Surathkal

Research Associate, Azim Premji Foundation

Vishmila Harshani Priyashadi

Center for Poverty Analysis

Prak Sereyvath

Cambodian Institute for Research and Rural Development (CIRD), Cambodia

Nicholas John Karani

Kenya Marine and Fisheries Research Institute, Kenya

Nuwanthika Dharmaratne

PhD Candidate in Biodiveristy Management, University of Kent, UK (From September) . Current - Research Manager, Verité Research, Colombo, Sri Lanka

Saranie Wijesinghe

United Nations Development Programme in Sri Lanka